4-26-13: Annotating the News

Posted on | April 26, 2013 | Comments Off on 4-26-13: Annotating the News

Capacity building as a precursor to testing

The L.A. Times has seen the elephant in the room. In a switch from its past obsession with test score accountability, the paper editorialized on Monday that we ought to be paying more attention to what students are supposed to be learning and particularly to the roll-out of the Common Core of standards, which is supposed to take place in 2014.

The promise of the Common Core to provide deeper learning and better testing will work only if a matching curriculum and testing system is in place and if teachers are trained. “[A]t the rate California is going, it won’t be ready,” the Times said, echoing my fears and an EdSource commentary by Arun Ramanathan

We need to build capacity before we rush to implement the Common Core and point fingers at those who, given the current preparedness, will surely stumble over its complexities. The Times said as much:

Experts are divided over the value of the new curriculum standards, which might or might not lead students to the deeper reading, reasoning and writing skills that were intended. But on this much they agree: The curriculum will fail if it isn’t carefully implemented with meaningful tests that are aligned with what the students are supposed to learn. Legislators and education leaders should be putting more emphasis on helping teachers get ready for common core and giving them a significant voice in how it is implemented. And if the state can’t get the right elements in place to do that by 2014, it would be better off delaying the new curriculum a couple of years and doing it right, rather than allowing common core to become yet another educational flash in the pan that never lives up to its promise.

There oughta be an immigration law!

A decade ago Samuel Huntington declared that the “Hispanic challenge” would threaten our historic values. Latinos, he asserted, were just too different to assimilate into the U.S. [A small aside: family historians found that our forebearers worshiped in German for at least the first 50 years after coming to America.] This week, a pair of dispatches suggested just how wrong he was about Latinos and immigrants in general.

In the New York Times, David Leonhardt reported on the remarkable progress of Latino immigrants, comparing first and second generations: College graduation up from 11% to 21% compared to 36% for the population at large; less than high school education down from 47% to 17%; median income up from $34.6 thousand to $48.4 thousand. James P. Smith at RAND calls Latinos “the new Italians,” like the immigrants from a century ago that arrived poor and undereducated. And like Italians, Latinos are rapidly intermarrying with other Americans: up from 7% in the first generation to 26% in the second.

Meanwhile, the Economist underscores the extent to which highly educated immigrants have pushed our economy. Forty percent of the high tech companies in California were started by immigrants, most famously, Google, whose co-founder Sergey Brin moved to the U.S. from Russia as a child.

Both stories underscore the necessity of an immigration law, not to be “nice” to immigrants, but to benefit the nation. As Leonhardt writes, illegal status “brings enormous disadvantages that inhibit climbing the economic ladder.” At the same time, current law allows only 250,000 foreign nationals with special skills into the country, less than one-tenth of a percent of the workforce, into the country annually. “America’s job-generating machine cannot run at full throttle for long if it is starved of fuel,” the Economist argues.

Of MOOCs and mentors

It’s hard to go through a day’s emails without seeing reference to Massive Open Online Courses. More than 5-million students have registered online for free or inexpensive courses run by Coursea, Udacity, or edX. But as A. J. Jacobs writes in the New York Times, you can forget about the Socratic method.

One may get the wisdom of first-rate professors, but you don’t get the professors. Jacobs signed up for 11 courses, and graded the whole experience with as a B, but personal interaction only got a D, writing: “Coursera and its competitors will have to figure out how to make teachers and teaching assistants more reachable. More like local pastors, less like deities on high.”

And that’s an important point. Teaching, both K-12 and college, has always been a bundled experience of instruction, assessment, and guidance. MOOCs, which are essentially a sophisticated broadcast media, may present very good lectures and ancillary material much more cheaply than conventional schools and colleges, but they’re not the medium to change young lives.

Although the two stories don’t reference one another, the same section of the N.Y. Times, carries a moving eulogy by writer Philip Roth for his high school teacher. Bob Lowenstein became a mentor and friend, a reader of Roth’s drafts and a writer of poetry. He also became a (slightly disguised) character in Roth’s book “I Married a Communist,” the subject of which, “is at bottom, education, tutelage, mentorship, in particular the education of an eager, earnest and impressionable adolescent in how to be come—as how well not to become—a bold and honorable and effective man.”

One may get great lectures, even great simulations from a MOOC, but they won’t grow you up. Nor will you go speak at a MOOC’s funeral.

Tags: Common Core > David Leonhardt > Economist > Immigration > L.A. Times > MOOC > N.Y. Times > Philip Roth

Higher Education Faces an “Avalanche”

Posted on | April 24, 2013 | Comments Off on Higher Education Faces an “Avalanche”

A new report by Sir Michael Barber and his colleagues at Pearson, Katelyn Donnelly and Saad Rizvi, should be on the reading list of everyone thinking about the future of higher education.

An Avalanche is Coming describes—somewhat breathlessly—the forces that are about to reshape colleges and universities worldwide. Globalization and technology are game changers, they argue. Barber, Donnelly, and Rivzi channel both Tom Friedman’s flat world and Clayton Christensen’s ideas about disruptive innovation.

But to a greater extent, they are channeling their own experience. Few people on the planet have the experience and access to the highest levels of power and discussion about education policy as these three. They have strapped themselves into a lot of airplane seats.

Barber has practiced education policy at the highest levels for three decades. His Education in the Capital became a keystone for the Blair government in the United Kingdom, in which he served. Then he headed the global education practice unit at the consulting firm McKinsey before moving to Pearson, where he heads their worldwide program of research into educational policy. Most recently, he has taken on one of the toughest jobs in the world, designing an education system in Pakistan.

Donnelly leads the Affordable Learning Fund that invests in early-stage companies that are developing low cost solutions for the developing world. Rizvi leads Pearson’s efforts at efficient delivery of educational outcomes. Thus, what’s notable about Avalanche, is the worldview of the authors and their position as both thought leaders and movers and shakers in education.

So, what does this transformative snow slide look like? Mostly, it looks like a fortress with the walls breached and the marauders, well, marauding. Territory that colleges and universities claimed as their own, sometimes in ringing Biblical city-on-a-hill language is becoming contested as:

- Universities and colleges compete with one another across state and national borders.

- Traditional higher education institutions compete with corporations, think tanks, and employers to offer both basic occupational training and high-level specialties.

- Non-degree learning becomes valued equally with degrees offered by traditional institutions of higher education.

It is not just easy information access that is new, although I still marvel at my ability to “go to the library” at 2 am or have more computing power in my phone than did the university computer into which I fed punched cards a half-century ago. Just as Barber, Donnelly, and Rizvi look at the Internet and declare content to be ubiquitous, so did John Dewey in School and Society more than a century ago when he wrote:

A high‐priesthood of learning, which guarded the treasury of truth and which doled it out to the masses under severe restrictions, was the inevitable expression of these (historic) conditions. But as a direct result of the industrial revolution of which we have been speaking, this has been changed. Printing was invented; it was made commercial. Books, magazines, papers were multiplied and cheapened. As a result of the locomotive and telegraph, frequent, rapid and cheap intercommunications by mails and electricity was called into being. Travel has been rendered easy; freedom of movement, with its accompanying exchange of ideas, indefinitely facilitated. The result has been an intellectual revolution (1900, p. 23).

That earlier democratization of knowledge ushered in the largest expansion of universities and colleges in history. But it also profoundly reshaped both their utilitarian and social missions. Universities became gatekeepers for occupations, the pathway to social and occupational status, and the engine that drove economies.

To me, the power of the coming avalanche lies in the unbundling of the university’s historic functions of teaching, research, and societal service. This model of university, what the University of California president Clark Kerr was to call a multiversity, is possible because of enormous cross-subsidization. Tuition supports much more than direct instruction. Undergraduate teaching supports graduate students doing research. Research grants support students and faculty supplying resources for teaching. Research also draws star faculty, enhances reputation, and draws more research funds, which are highly concentrated in elite institutions. The presence of colleges and universities changes communities, including the desirability of neighborhoods and the price of real estate.

And in many ways, universities become basic industries, driving the economies of regions, states, and, sometimes, whole nations. Barber, Donnelly, and Rizvi cite Stanford at the grain of sand that started Silicon Valley, but there are scores of other examples including the decidedly non-elite community colleges that have had a profound effect on their surrounding communities.

Unbundling the three historic functions, puts the institution at risk, and that is the point of Avalanche.

It’s a good read, and it lifts the veil a bit about the future of higher education from three people who are busy bringing it about.

Tags: Avalanche > Clayton Christensen > Higher Education > Michael Barber > Pearson > Tom Friedman

D.C. School Cheating Issue Calls Test-Driven Incentives into Question

Posted on | April 22, 2013 | Comments Off on D.C. School Cheating Issue Calls Test-Driven Incentives into Question

This post can also be found at EdSource

The smoke surrounding allegations of test score cheating in the Washington, D.C public schools burst into flame last week. In a 4,300-word blog post, titled Michelle Rhee’s Reign of Error, the veteran educational journalist John Merrow linked the former schools chancellor with documents that suggest that she knew about widespread cheating on standardized tests and looked the other way.

Merrow drew parallels between Washington and Atlanta, where former superintendent Beverly Hall and 34 others have been indicted. But the underlying question is whether school reform can successfully be driven by rewards and punishments tied to standardized tests.

First, the Watergate question: what did Rhee know and when did she know it? As U.S.A. Today reported, District of Columbia Public Schools officials have long maintained that a 2011 test-cheating scandal that generated two government probes was limited to one elementary school. Merrow, however, reported that a long-buried memo from an outside data consultant warned as far back as January 2009 that educator cheating on 2008 standardized tests could have been widespread, with 191 teachers in 70 schools “implicated in possible testing infractions.”

Consultant Fay G. Sanford noted substantial numbers of erasures on test forms where corrections were made from wrong answers to correct ones. (Erasers leave smudge marks that the machines doing the grading recognize along with the answers.) “It is common knowledge in the high-stakes testing community that one of the easiest ways for teachers to artificially inflate student test scores is to erase student wrong responses to multiple choice questions and recode them as correct,” Sanford wrote.

When asked, Rhee said that she didn’t recall getting a memo from Sanford an assertion she repeated last week to the Los Angeles Times editorial board.

A day after the Merrow report was issued, another investigation was released citing “critical” violations of test security in 18 classrooms located in 7 district schools and 4 charters. The test was given in more than 2,600 classrooms, and current D.C. schools chancellor Kaya Henderson said in a statement, “We are pleased that this is yet another investigation that confirms that there is no widespread cheating at DCPS.”

But Henderson is not quelling demands for a district-wide investigation. Randi Weingarten, president of the American Federation of Teachers, has called for an independent investigation as did Washington Post writer Valerie Strauss, who said, “The memo does not offer conclusive evidence that cheating occurred, but it literally begs for a thorough probe to be conducted — this time by investigators with subpoena powers.”

Meanwhile, an in-depth evaluation of D.C. schools by a National Research Council panel continues. The study is chaired by two Californians: Carl Cohn, a professor at Claremont Graduate University and member of the state school board, and Lorraine McDonnell, a professor of political science at U.C. Santa Barbara. Their work is not confined to test tampering, but considers the overall effect of governance and management changes. Read more

Tags: Carl Cohn > Claremont Graduate University > District of Columbia Schools > John Merrow > Lorraine McDonnell > Lynn Stout > Michelle Rhee

Big Money and the School Board: An Annotation of a “L.A. Times” Op-Ed

Posted on | March 11, 2013 | Comments Off on Big Money and the School Board: An Annotation of a “L.A. Times” Op-Ed

[This story has also been posted at Ed Source.]

The Los Angeles Times Monday printed an op-ed piece I wrote about last week’s school board election, where a coalition of deep pockets givers spurred by Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa spent over $63 per vote. It was not only big money but also money badly spent. (Read the whole article.)

The 800-word limit for op-eds is about double the normal readership attention span, but it doesn’t allow much amplification of the basic points.

One point I raised was the crafting of a Democratic alternative to the Republican position on teachers unions, which is largely that they should be weakened by restriction on bargaining rights. Generally, this is done by limiting the scope of bargaining or the ability to collect union dues.

Unions fight these restrictions hard, as they should: witness the failed recall election against Gov. Scott Walker in Wisconsin.

Meanwhile, the political division among the self-styled reformers and the unions continues. Both call themselves Democrats. The list includes mayors, such as Villaraigosa and Chicago’s Rahm Emanuel. New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg, now registered as an independent, contributed $1-million to last week’s Los Angeles Unified School District board election.

The logic of the reformers seems to be that teacher unions are so wrongheaded, and the citizenry sufficiently tired of fights about seniority and teacher evaluation, that putting forward a slate of school board candidates is the way to change the balance of power in the school district and mute the pesky union.

But the strategy hasn’t worked. Not in L.A., not in Washington, D.C., not in Chicago.

In the op-ed piece, I suggested changing strategy. Instead of attacking the unions via the school board, rewrite labor law so that it makes unions responsible for education quality.

This issue needs lots of discussion, and I hope the op-ed will engender some, but the big point is that unions now do what the law requires of them. They negotiate wages, hours, and conditions of employment. Nothing requires them to negotiate educational quality.

During the 2012 presidential campaign, Mitt Romney characterized teacher unions as uncaring about education quality quoting the late American Federation of Teachers President Albert Shanker as saying “When school children start paying union dues, that’s when I’ll start representing the interests of children. ” Problem is, Shanker never said it, or at least no one can verify that he did. Actually, Shanker cared a lot about educational quality and spent at least the last decade of his life working to use unionism as a vehicle for change.

But the point is that unions are not empowered or required to represent the interests of children. Indeed, the construction of labor law crimps teacher professionalism. And the restrictions in labor law advocated by Republicans generally make teachers less professional rather than more. Remember: profession is a collective characteristic rather than an individual work ethic. Organized professions, not individuals, set training standards, codes of conduct, licensing regulations, and standards of practice.

So, how does one get labor law pointed toward supporting teacher engagement in standards setting? Read more

Tags: Albert Shanker > Labor Law > Michael Bloomberg > Scope of bargaining > Teacher evaluation

Rainy Day Musing about Tests and Property Rights

Posted on | February 8, 2013 | Comments Off on Rainy Day Musing about Tests and Property Rights

It’s a rainy day in Claremont: a good day to muse over the blogs and emails.

Teacher boycotts of standardized tests in Seattle have taken a new turn. District superintendent José Banda has ordered administrators at Garfield High School to give the tests instead of the teachers giving them, according to The Seattle Times. At the same time, many students are opting out of the tests, and the school’s parent association is organizing to notify parents of their right to withdraw students from them.

The standardized test boycott has spread to Portland where a group of students is urging test boycotts, and Jackie Zubrzycki reports on the Education Week blog “District Dossier” that the movement is growing.

The protests may lead to a game of educational chicken, where districts and schools demand that students take tests in order to graduate, and students threaten sabotage the results by doing poorly on purpose. The upside of all this is that both in Portland and Seattle, the protests have given rise to a reexamination of the value of standardized tests. In an educational policy world that claims (often without justification) to be “evidence based,” what counts as evidence, how it is collected, and how it is measured is extremely important and should be the topic of political debate.

On this point, see Michael Apple’s review of the a 2010 book Understanding Education Indicators: A Practical Primer for Research and Policy by Michael Planty and Deven Carlson. I’ve not yet read the book, but understanding clearly what these tests can and can’t tell us about student learning ought to be part of the core skills of every school administrator and teacher leader. And as Apple, in his usual fashion, points out, the construction and mandating of tests is not politically neutral act.

And all this comes as the country lurches toward the Common Core standards and its associated tests.

File this Under Selling Young Picassos. The Prince George’s County, Maryland, school board has voted to assert ownership of teacher and student work. So, just in case you thought your 1st grader’s drawing was cute, you may have pay the school to send it to grandma. According to a Washington Post story by Ovetta Wiggins, the move was prompted when two school board members went to an Apple Computer presentation on how teachers can use apps to create new curricula. And they figured that the schools ought to own the product. Maybe they overreached a bit.

Tags: District Dossier > Education Week > Michael Apple > Portland > Seattle > test boycott

Further Thoughts About Teacher-Run Schools

Posted on | February 1, 2013 | Comments Off on Further Thoughts About Teacher-Run Schools

The discussion about teacher-run schools prompts me to jot a bit about why I am fascinated by this small, iconoclastic form of organization.

I am, first of all, simply charmed by the schools I visited. They are interesting places full of interesting people—both faculty and students. There is a vibe and intensity to being there. At the same time, it is easy to recognize that these schools are not for everyone. Not all students thrive in them; not all teachers would want to work in them.

Why, then do we care? Teacher-run schools demonstrate capacity. They demonstrate that both teachers and students have much greater capacity to monitor and control their own work than the existing system asks for or allows. They create schools that are flexible and responsive rather than built around layers of regulations, compliance mandates, and inspection.

When teachers run their own schools, the pedagogy is different. The word authentic became trite education-speak, but it applies well to the teacher-run schools I visited. Students do real work and real projects. The schools have classes when they need them: direct instruction, after all, is a fairly efficient way of transmitting information. But for the most part, students work on doing, building, creating, and for the most part they are not bored while they are working. School actually motivates students.

Assessment is different, too, rooted in examination of student products and an overall sense of whether the student is thriving and making progress, the education equivalent of holistic medicine. These schools do not exist for the purpose of test score maximization.

When teachers run their own schools, they create better jobs for themselves, but not in the selfish sense. Because they understand the economics of the school at its elemental level, they temper self-interest, often denying themselves raises. They live in a more fragile economy without the job protections that civil service provides for teachers in district schools. They work hard, and frequently long. And nearly all the teachers I talked to said that the jobs they have now are the best ones that they had ever had. Less security and more satisfaction create an interesting juxtaposition.

The craft skills these teachers display are much more consistent with 21st Century information production than they are with early 20th Century industrial production, on which contemporary school systems are modeled. And the organization skills create small, cellular units capable of independent operation. That’s fascinating because it suggests creating a teaching occupation that is consistent with how people access and use information in our age.

“I would prefer to trust our teachers…”

Posted on | January 25, 2013 | Comments Off on “I would prefer to trust our teachers…”

California’s Back! Gov. Jerry Brown did himself proud in Thursday’s state-of-the-state speech, and he did California proud, too. In the details of the speech, there are prospects for boldness, greatness, and innovation, not the tire patching and gridlock we’ve experienced as government.

Others will comment in great length on the wisdom of the San Joaquin delta tunnel project and whether high-speed rail is prescient or folly. And educational interests are putting the pencil to whether they win or lose under the governor’s plan for simplifying public education funding and regulation. (See David Plank’s Los Angeles Times commentary.)

Instead of joining these conversations, or commenting on the literary illusions in the governor’s speech, please zoom in one sentence that has revolutionary importance: “I would prefer to trust our teachers who are in the classroom each day, doing the real work—lighting fires in young minds.”

Brown knows that we live in a world that profoundly distrusts teachers. Most of what passes for education reform has been crafted with the assumption that teachers are incompetent or malfeasant. Education systems, therefore, are layered with micromanagement rather than characterized by useful feedback mechanisms that make teachers smart about their work. It bends the mind to contemplate what a radical change would be required if public education were built around high-trust assumptions.

But there are places that trust teachers with substantive decisions and hard-nosed accountability. I’ve written about some of them, including the Avalon School in St. Paul, and in a new book Trusting Teachers with School Success, Kim Farris-Berg and Edward Dirkswager describe practices that build high commitment and performance in schools where teachers: Read more

Tags: Edward Dirkswager > Jerry Brown > Kim Farris-Berg > Teacher Run Schools

Three Modest Suggestions About Technology Policy

Posted on | November 20, 2012 | Comments Off on Three Modest Suggestions About Technology Policy

Last Friday, I presented some of my thoughts about educational technology at the Policy Analysis For California Education seminar at Sacramento. I began by asking the same question that I’ve asked myself and others over the last couple years: “Why should California, the headwater of the digital revolution, be stuck in the eddies of early 20th Century school design?”

There is no good reason, only political will, and the inability to find a clear enough vision to create public policy that will work. That, as it turns out, is a tall order.

People are more afraid of giving up control than they are excited about the possibilities of technology. Although educators frequently denigrate standardized testing, they remain wedded to standardized learning: a single scope and sequence, age and grade leveled. It will take some doing to disturb the existing grammar of schooling.

Technology to change learning does not yet have a champion. This is not to say that there are not advocates for technology usage, particularly among the companies that manufacture hardware and software. But we miss “the city on the hill vision” connected to the political vision to bring it about.

I made three policy suggestions at the seminar:

- Improve those places in the existing system that are most troublesome and expensive. In California, as in most of the rest of the country, these include the education of English Language Learners, Special Education, remediation at all levels, and the transition from high school to college.

- Start to build a web-based educational infrastructure available to all students, teachers, and families in the state. It would do three things. It would create access at school and at home thus partially bridging the digital divide between rich and poor. It would broker and rate lessons and teaching resources. And it would allow students to take examinations and get credit when they are ready.

- Tweak regulations in order to create a more open system with greater incentive for participation and innovation.

The slides from my talk are available along with a video of the PACE presentation.

Some Post-Election Thoughts about God’s Politics

Posted on | November 10, 2012 | Comments Off on Some Post-Election Thoughts about God’s Politics

In the run-up to the election season, I gave a little talk based on Jim Wallis’ book God’s Politics, extending his ideas about prophetic politics—“not future telling, but articulating moral truth”—to big-issue organization in congregational and community life. That talk, including stories of the prophets in my own life, is available by clicking here.

But the election is over, and musing about God’s Politics will take place within the context of the results.

This was a turning point election, like Roosevelt in 1932 or Reagan in 1980, which defines the country and its direction. Even more than 2008, it illustrates that beneath the money-fueled hate speech and engineered paranoia, the United States is a vast, tolerant, and reasonably forward thinking country.

The diverse winning electorate represents a new dominant force in public life, perhaps a long lasting coalition that will rival FDR’s without the taint of the old Southern Democrats. Social and demographic change was the key to the election. It was not that Governor Romney failed to energize white voters; he did as well as any Republican. But they were not enough.

Obama’s win was remarkable on several fronts. He had a lot going against him. The economy has been sluggish, and the President bore some responsibility for that. No incumbent president has been elected with unemployment as high as ours. He faced intense ideological backlash in 2010 that was not effectively countered until this year’s campaign was in full swing. Even then it came at the self-destructive hands of his opponent, who scrambled so far to the right to win the nomination that he couldn’t Etch-a-Sketch it away. Even his autumn rebirth as a moderate could not erase the “47%” and “self-deport” statements that were an accurate reflection of the values of his base.

Through all this, God was invoked frequently but I am not sure our heavenly parent was well listened to. Read more

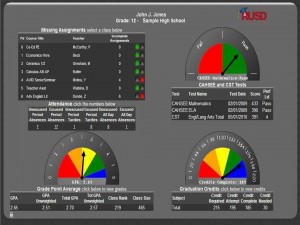

Musings About Educational Dashboards: They’re About More Than Green Lights

Posted on | July 17, 2012 | Comments Off on Musings About Educational Dashboards: They’re About More Than Green Lights

I’ve been doing some musing about educational dashboards lately, the displays that school districts and others are developing to provide quick indicators of success or failure.

The iconography, of course, is derived from the dashboards in our automobiles, and we understand the self-correcting nature of those indicators. People who don’t heed the “tank empty” light frequently find themselves over at the side of the road calling the service truck. Zipping past the nice state policeman when the speedometer is pegged at 87 is likely to be expensive. Will this same kind of real-time information be useful in education? If so, what information should students, teachers, and parents get?

The Riverside Unified School District—one of California’s leaders in things digital—has created the five-indicator dashboard illustrated here. A student and, perhaps more importantly, his or her parents can know whether assignments are missing or classes skipped. The California High School Exit Exam and credits earned toward graduation show up in other gauges.

Vendors of what are called Learning Management Systems are developing dashboards like crazy, and the Michael and Susan Dell Foundation have built a powerful engine called ed-fi that sits behind the dashboard and connects it with school, district, state, and vendor systems. Meanwhile, as Frank Catalano reports on Mind/Shift, the Council of State School Officers is hard at work creating a multi-state Shared Learning Collaborative, a big-bucket data warehouse that would be free to states and districts. They are also developing spigots for the buckets, apps that students and teachers could use to get data out.

The dashboards and the engines behind them are linked to an assumption that better data will yield better schooling. Educators frequently observe that a great deal of information is available in schools, but teachers and students seldom use it. There is stuff that teachers don’t know about their students that arguably would help them—things such as the pattern of mistakes students make in solving math problems—and there are things that students should know to help themselves, such as how to stay on the pathway to college.

Thus, it’s easy to make strong case for dashboards as important devices to feed back data to students and schools. Making complex data actionable ought to be one of the benefits of computer technology for learning.

That said, the current crop seem pretty limited, and overreliance on dashboard data can create horrible goal substitution in which turning all the dashboard lights green equates with learning or a good education. (There are also bunches of privacy issues that I won’t deal with here.)

A better, less limited, dashboard would be personalized. Data elements should work like Widgets or elements on a computer home page. A student who is has passed the high school exit exam and is aiming toward Cal or Harvey Mudd doesn’t need the CAHSEE icon staring him or her in the face. Let students get the gauges they need.

We do that with car dashboards. Even my seven-year-old auto lets me change the displays, and as Claremont Graduate University alum Mark Maine, who knows a thing or two about cars, writes:

Racecars can both send and receive data…lots of data. For the driver, the instruments, including things like shift lights, tell him/her about their performance with detailed info on sector and lap times. They have this type of technology at the go-kart level all the way up to Formula 1. In addition, teams can monitor the car’s performance including tire pressure changes and share that info with the driver so he or she is constant two-way communication, like real time Onstar. Finally, teams collect and analyze tons of data from different parts of the car to improve the car’s set up for a particular track and driver. They also pay a great deal of attention to what the driver has to say about the car’s performance and track behavior.

Consider the elements of racecar dashboard and the data system behind it: First, a great deal of data is analyzed in real time. Both the driver and the crew analyze and react to data. The crew customizes the car for each race and each driver. The crew listens carefully to what the driver says about his or her experience. The data are useful because they are current, all parties know what to do with them, and the parts of the system communicate, both electronically and in person.

We have only begun to develop similar adaptive capacity with educational data. Thus, the first dashboard danger is that the information will be irrelevant or static. If a dashboard doesn’t substantially improve information flows from those available in old-fashioned report cards, it isn’t worth the effort.

However, the greater danger in dashboards is that we come to confuse the variables they report with the goals of education. The goal of driving is not to keep from running out of gas, or to prevent the car from boiling over. Those are only conditions for keeping the car in motion. No one would confuse those indicators with a beautiful trip or a good driver.

When I was driving home from the office the other day I pulled up behind a car whose license plate holder said “E X C U S E me for driving the speed limit.” Actually, the driver was loping along at about four mph under. I am sure the driver was as pleased with all the green light indicators on his dashboard as he, oblivious to his surroundings, held up a line of traffic all the way through town.

It is highly likely that uncritical policy viewers and school administrators will engage in the same kind of goal substitution. Making all the indicators turn green is not the same as learning. But the better we get at creating and customizing dashboards, the more proximate the two will be.

(I’m looking for good examples of real time indicator systems, and would appreciate reader suggestions.)

Tags: Dashboards > Frank Catalano > Michael and Susan Dell Foundation > Mind/Shift > Riverside Unified School District